Welcome to the Teasers page

The Geometry tab diplays all the teasers related to the composition of the Last Supper.

The Symbolism tab offers articles on the symbolic meaning of the first four numbers.

Why not share a teaser with your followers on social media using the sharing buttons?

Welcome to the Teasers page

The Geometry tab diplays all the teasers related to the composition of the Last Supper. The Symbolism tab offers articles on the symbolic meaning of the first four numbers.

––Some of the pictures will show an overlay when hovered with a mouse. Click to expand them. ––

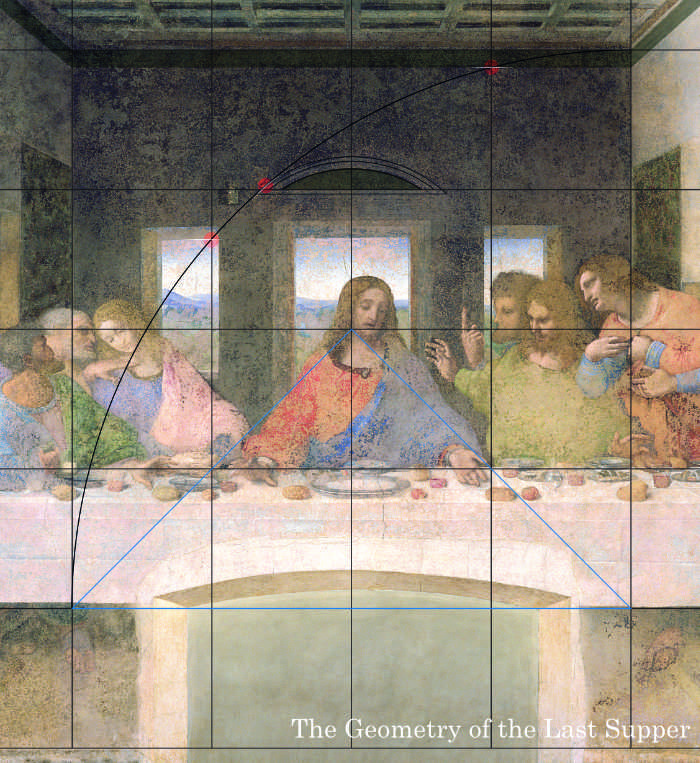

Overture

The rotation of the base of the triangle is interesting for 3 reasons.

The first intersection of the arc with the grid corresponds to the height of the window.

The arc is tangential to the curve of the pediment above the door.

The last interesection of the arc with the grid gives the height of the cornice, just below the ceiling.

Breaking the Law

The Early Renaissance discovery of linear perspective was a major breakthrough which revolutionised the visual arts. For the first time, painters were able to represent objects receding into the distance with accuracy.

In short, the idea is to draw on the canvas a checkerboard which consists of converging lines called orthogonals and an array of parallel horizontal lines called transversals.

As the eye moves towards the centre of the composition, the gap between the transversals becomes progressively narrower contributing to a sense of depth. The orthogonals, however, converge toward a single point called the vanishing point which defines the height of the horizon.

We can only imagine the enthusiasm that the discovery of perspective must have generated amongst Renaissance painters. For the first time in history, the illusion of volume and depth could be represented correctly, adding a whole new dimension to painting.

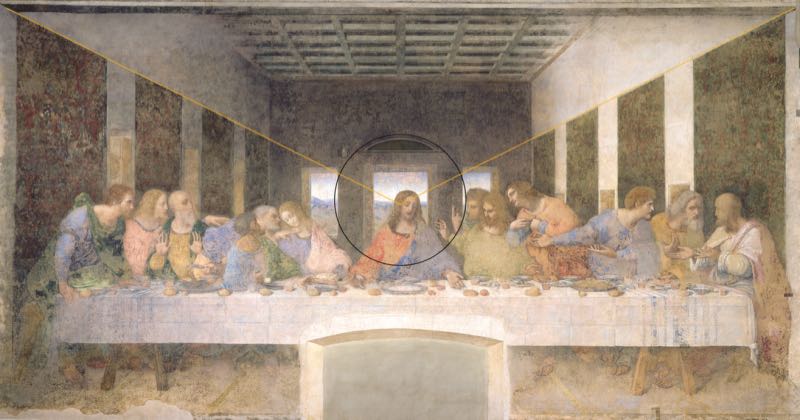

In the Last Supper, the strongest sense of depth arises from the tall tapestries hung on the walls. They offer vigorous perspective lines which converge to the vanishing point situated on Christ's head.

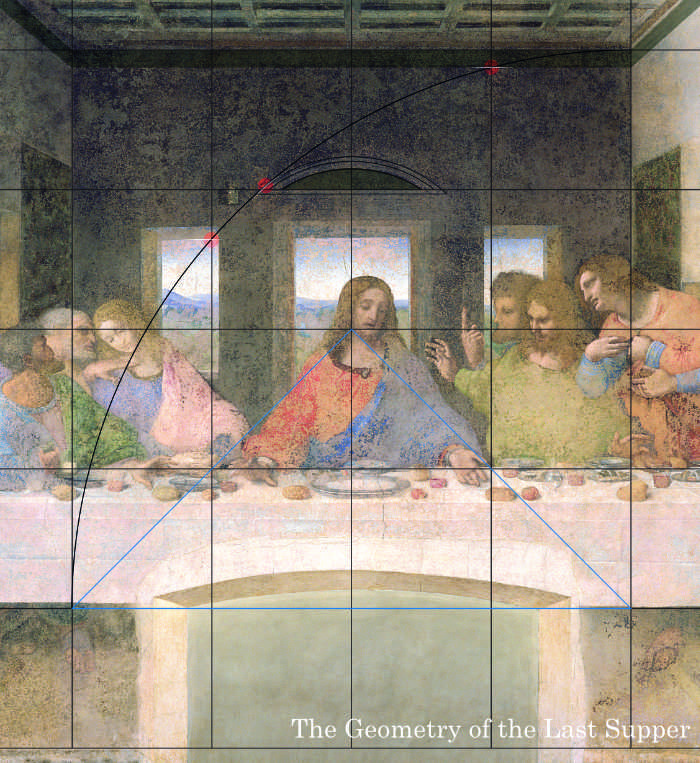

Natural light enters the dining room through a central door and two windows. A detailed inspection of the windows shows that their construction astonishingly transgresses the laws of perspective established only sixty years before Leonardo da Vinci started working on the Last Supper.

Here, the non-compliance is easily proved by tracing the perspective line that passes through the corner of each window (white lines) where the thickness of the wall is apparent. The wall thickness should be following its own orthogonal towards the vanishing point.

However, the painted perspective clearly differs from the theoretical line (the discrepancy is shown in red).

The perspective used for the windows and the door is therefore incorrect. Did Leonardo resort to some other logic significant enough to justify this emancipation from a strict obedience to the theory of perspective?

Action Shot

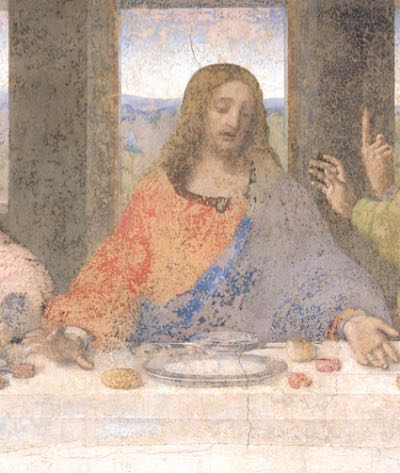

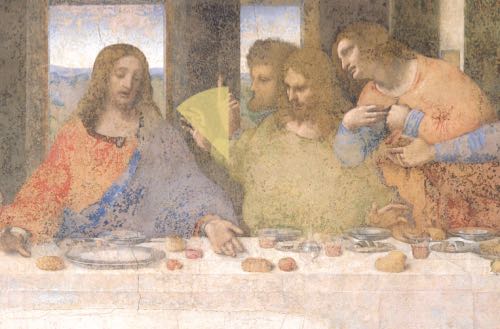

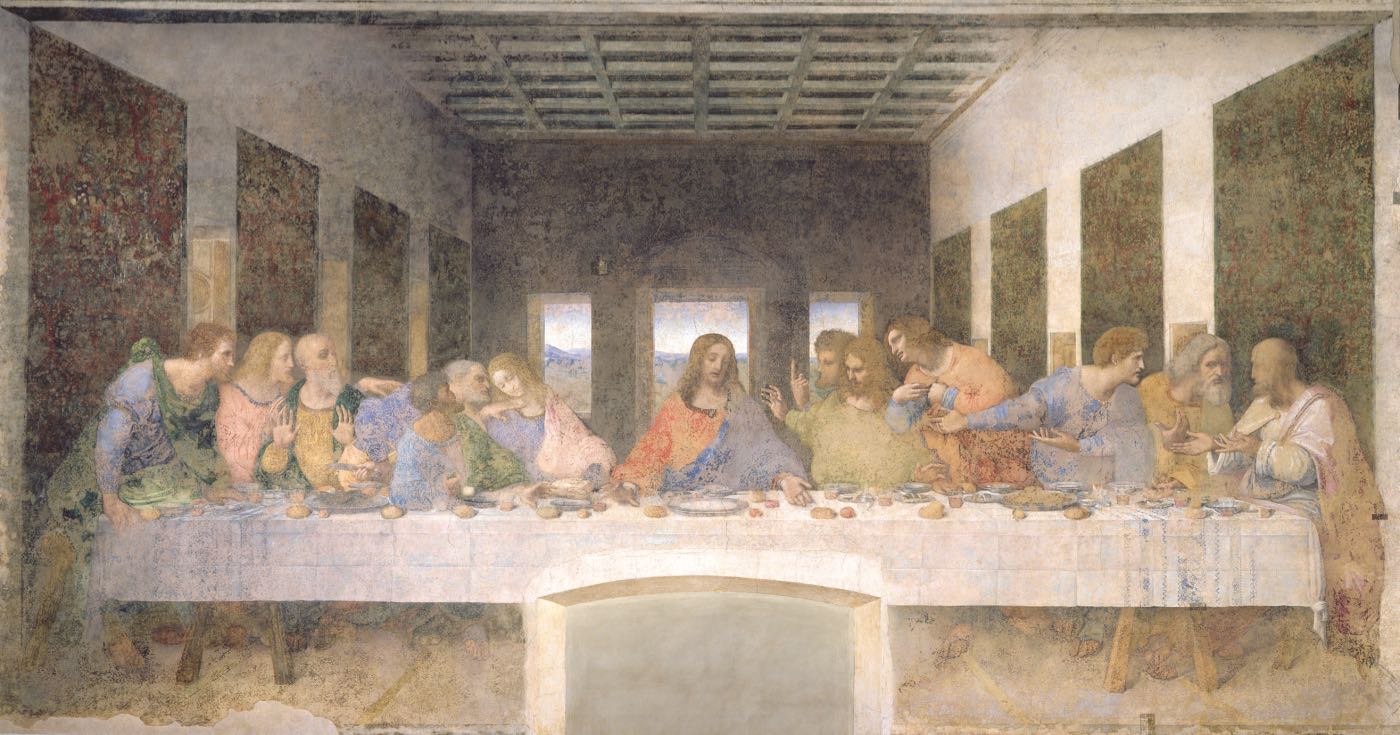

The Last Supper is like a snapshot. Something has just triggered the vast array of emotions shown by the disciples. Jesus remains calm and composed, his arms open before him. What is happening?

The instant painted by Leonardo da Vinci corresponds to verse 24 from the thirteenth chapter of John’s gospel. The disciples are reacting violently to what their master has just announced to them: ‘Truly, truly, I say to you, one of you will betray me’ (John 13:21).

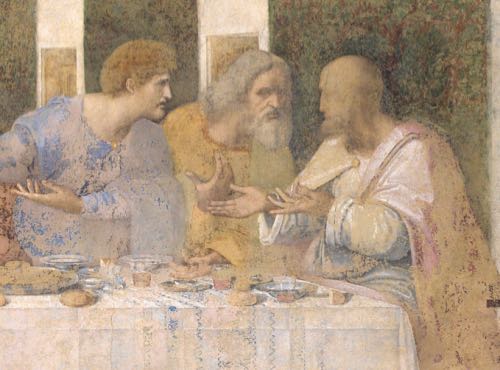

Peter, leaning behind Judas, gets John’s attention and whispers in his ear, ‘Tell us who it is of whom he speaks.’

The answer to Peter’s question varies between the gospels. In John's gospel, Jesus indicated the betrayer by giving him a morsel of bread after dipping it. Matthew and Mark wrote: ‘He who has dipped his hand in the dish with me, will betray me’ (Matthew 26:23; Mark 14:20). Accordingly, Leonardo painted the right hand of Christ and the left hand of Judas having already initiated a movement towards each other which would lead, a moment later, to the meeting of their hands.

Hand gestures are wonderfully expressive in the Last Supper. Some of them might even be linked to the geometry of the composition ...

Who is Who

There are thirteen protagonists at the table of the Last Supper. A few of them are quite famous, but perhaps it would be good to introduce them all.

A keen eye will notice that the disciples form four groups of three. So let’s start with the group on the left.

First there is Bartholomew, then James the Minor, then Andrew, who has both hands held up before him.

In the next group Peter, holding a knife, is reaching behind Judas to ask John, ‘Tell us who it is of whom he speaks.’ Judas is about to grab a piece of bread while holding a purse in his right hand.

Jesus is seated in the centre. His calming presence is in stark contrast to the vehement agitation of the disciples.

The third group consists of James the Major, seated next to Jesus and angrily expressing his indignation; Thomas, his finger pointing towards the sky; and Philip, standing with his hands on his heart.

Finally, Matthew, Thaddeus, and Simon share their disbelief.

As we will see a little later, these groups are organised in a very specific way.

A Matter of Perspective

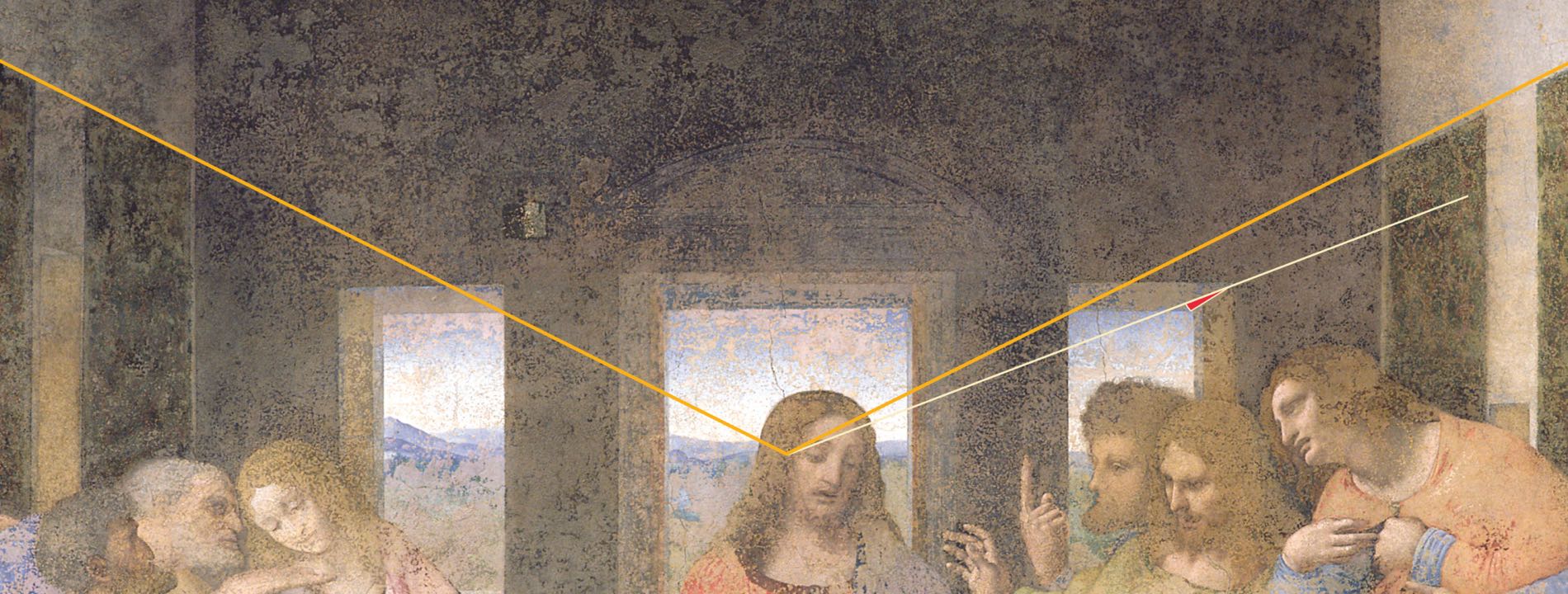

In order to accommodate the long table of the Last Supper, Leonardo da Vinci made the room as wide as possible in the foreground. The only indication of the floor size lies behind Simon who is seated on the far right. In the lower corner of the painting, we can see where the tapestry meets the floor.

At first sight, it appears as if the bottom of the tapestry might be set on the perspective lines suggested by the tops of the tapestries. Let's have a look and extend them all the way down.

(Hover the mouse above the picture).

As we can see, the yellow line doesn’t quite reach the bottom of the tapestry.

How then did Leonardo define the width of the floor? The answer to that question is one of great beauty.

The Pediment

Above the door, there is a decorative pediment which unfortunately is now only faintly visible. Even during Leonardo da Vinci’s lifetime, the mural of the Last Supper was showing signs of degradation. This is due to Leonardo being reluctant to use the well-established al fresco method for his mural. Painting al fresco means that the painter must work relatively quickly. Adjustments can be made only when the paint is still fresh. Once it has dried, retouching the painting becomes almost impossible. Leonardo wanted to be able to take his time and come back to his work as and when it pleased him. For that reason, he devised a recipe which proved ill-fated at withstanding the decaying influence of time.

In 1770, a restoration of the Last Supper was undertaken which consisted of repainting over the majority of the work! About 200 years later, in 1978, began a 21-year-long restoration aimed at removing the added layer of paint in order to reveal the original pigments. In certain areas of the mural, very little of the original paint remains, as is the case with the circular pediment above the door. For clarity’s sake, I have redrawn the pediment as an overlay.

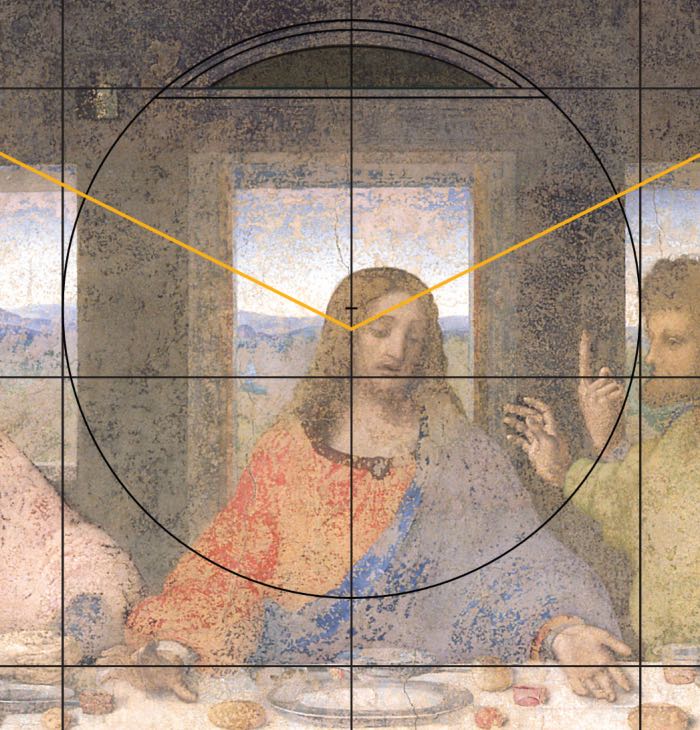

The pediment is important, at least symbolically, for this is the only circle in the composition of the Last Supper. One might expect the centre of the circle which forms the outer edge of the pediment to fall exactly at the vanishing point; however, it does not. The centre of the circle is placed a little higher than the centre of the perspective.

Is there any significance to this discrepancy between the centre of the circle and the vanishing point, or is it just down to luck? In reality, there is a geometrical and a symbolic reason for this, and all becomes clear once the meaning of the geometry is revealed.

The Key

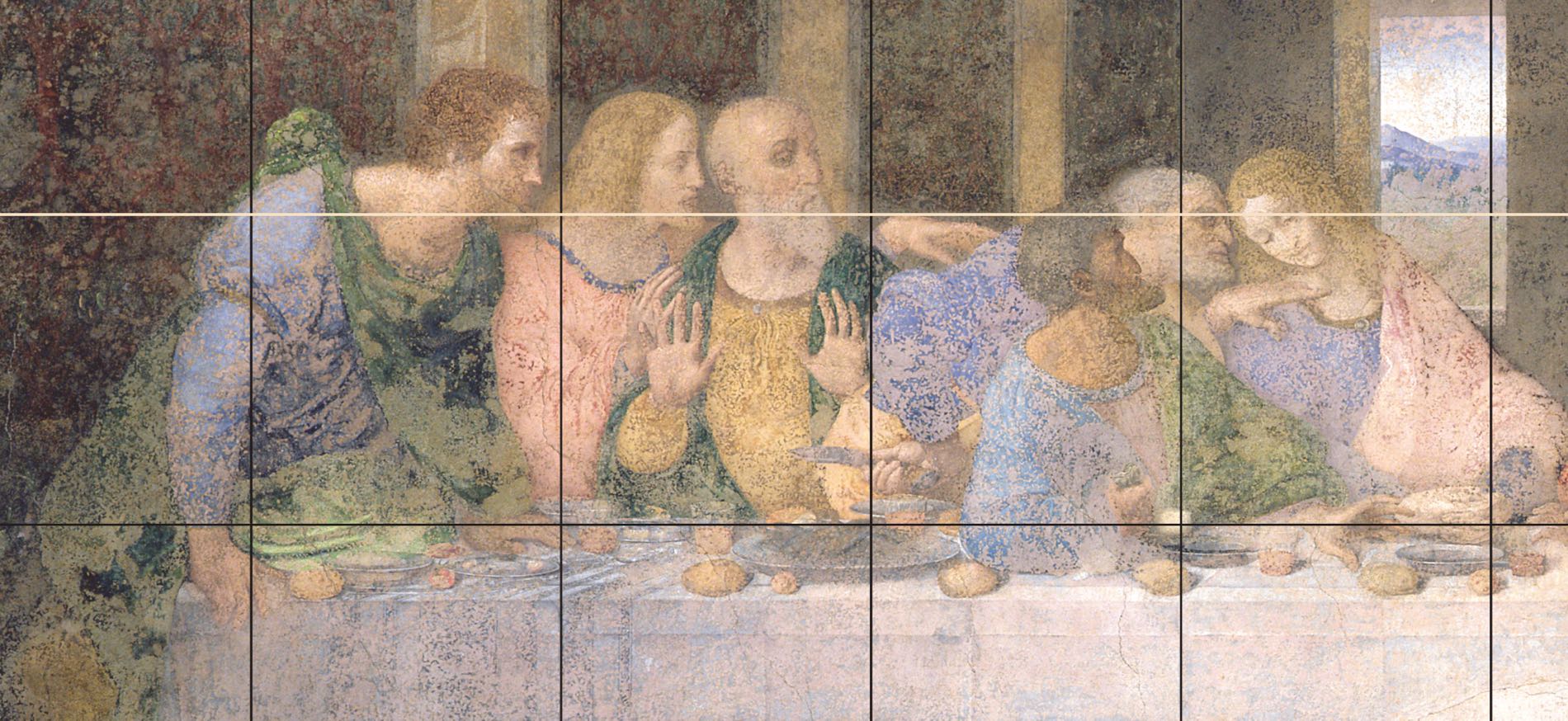

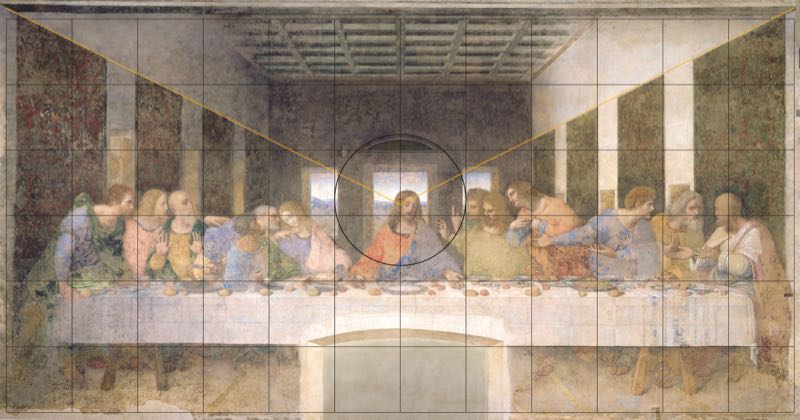

Probably inspired by the spacing of the beams that form the coffered ceiling, Thomas Brachert was the first scholar to draw a grid of 12 by 6 on a picture of the Last Supper. He was then able to make a few interesting observations.

Looking horizontally at the twelve units of the grid, Brachert notes that the tapestries are aligned with it and that the walls each occupy four units.

Vertically, Brachert observes the following:

• the coffered ceiling occupies one unit of the grid;

• the height of the back wall, from the top of the table to the ceiling, covers three units;

• the lowest two units of the grid are available for the floor of the dining room. The table itself fills one unit and runs across almost the entire width of the room.

Not only does the grid serve as a guide for the dimensions of the dining room, but it also commands the distribution of the apostles along the table. The disciples form four groups, two on each side of the central figure of Jesus.

Looking at their position in connection with the grid, Brachert points out that the groups located at the two ends of the table are given the space of three units on each side. The two groups closest to Jesus are confined to only two units each. This leaves two units in the centre occupied by Jesus alone.

The grid organises the general proportions of the dining room, but there are some important elements that aren't bound by its rule. That is obviously the case for the windows and the door, and this is where the fun begins. In effect, the grid is the key that will unlock the geometry of the Last Supper.

Median

Definition: Median of a quadrilateral

Segment that joins the midpoints of two opposite sides of a quadrilateral.

In other words, the two medians of the grid are the vertical and horizontal lines that intersect at its centre.

A study of the horizontal median releaves some interesting details about the Last Supper.

The median traverses the heads of the disciples. The only one to have his face below the line is Judas. Counterbalancing Judas’s downward motion, Philip rises above the line, hands on his heart.

James the Minor, belonging to the first group of apostles on the left, raises his hand, trying to get Peter’s attention. The palm is facing towards the floor and the hand is almost flat. His posture is such that the back of his hand is precisely at the level of the median.

- The median passes across the face of Jesus just below the mouth.

There is another hands configuration that could potentially trigger our interest: namely, the interplay between James’s and Thomas’s hands. They form an angle which is quite striking, and Thomas is pointing his index finger towards the sky.

Could it be that Thomas is trying to tell us something?

Three Centres for the Last Supper?

With the presentation of Brachert’s grid (cf. 'The Key'), things at first seem to get a little out of hand. Indeed, the grid has its own centre, and when we take into consideration the vanishing point as well as the circle of the pediment (which sits above the door), we realise that all these centres are located in different positions.

At first glance, the three centres don’t seem to be related to each other in any way. Yet it appears that the diameter of the circle which forms the outer edge of the pediment is equal to two units of the grid.

Thus a burning question arises: how were the lines of the perspective designed? Do they also relate to the grid?

The three centres are indeed part of a unique geometrical design. Not only is it beautiful in its efficiency, but it is the symbolic meaning concealed within these three centres which forms the core message conveyed by the geometry. This spiritual message is certainly hidden but nonetheless present, like a profound identity, at the heart of the Last Supper.

Pythagoras

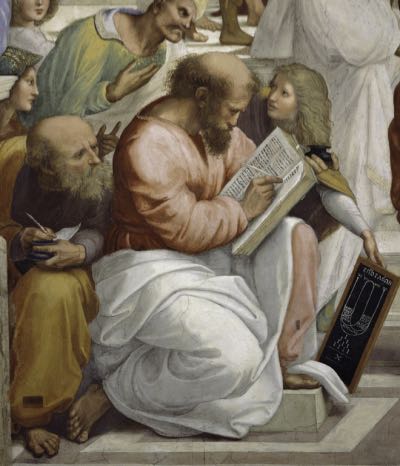

Recognised by some as the first philosopher, Pythagoras had a considerable impact on Western culture. Such was his influence during the Renaissance that it was thought Plato was his pupil.

The Greek philosopher was very highly regarded by Renaissance artists and thinkers. He is famously featured in Raphael’s School of Athens in the Vatican.

Pythagoras is shown writing a book while a youth presents a slate to him. Two diagrams are drawn on it.

The first (which looks like a U shape) relates to the musical ratios discovered by Pythagoras. His discovery led him to believe that there was an interrelation between the harmony found in music and the harmony of the cosmos. Pythagoras developed a concept he called the music of the spheres – which captivated the minds of men and women until the end of the Renaissance. According to this theory, the planets, the moon, and even the sun each emit a sound in relation to their orbital paths as they travel around a central fire. The celestial music resulting from the movement of the heavenly bodies (inaudible except to the wisest of people!) was thought to be a manifestation of God’s harmonious governance of the universe.

The second diagram will be the subject of the next post.

The revival of Pythagorean ideas peaked during the High Renaissance. It is remarkable that thinkers who belonged to different schools of thought all recognised Pythagoras’s authority and the importance of the discoveries attributed to him. The philosopher’s inclination to pursue virtue and wisdom and to lead an austere life appealed even to those members of the clergy who saw in him a predecessor to Christianity. During the Renaissance, some Christians were Pythagoreans: amongst them were priests, cardinals, and most probably two popes.º

Although Leonardo da Vinci never said much about himself, what is known of his reading, interests, and acquaintances strongly suggests that he held Pythagoras in high esteem.

º For more information on this subject, read Pythagoras and Renaissance Europe: Finding Heaven by Christiane Joost-Gaugier (Cambridge University Press, 2009).

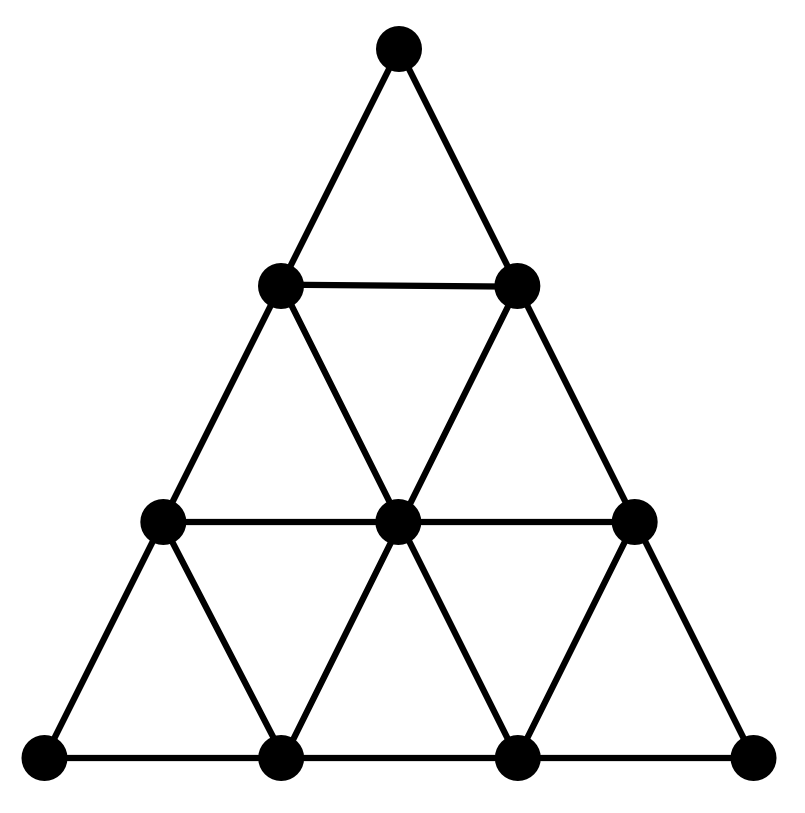

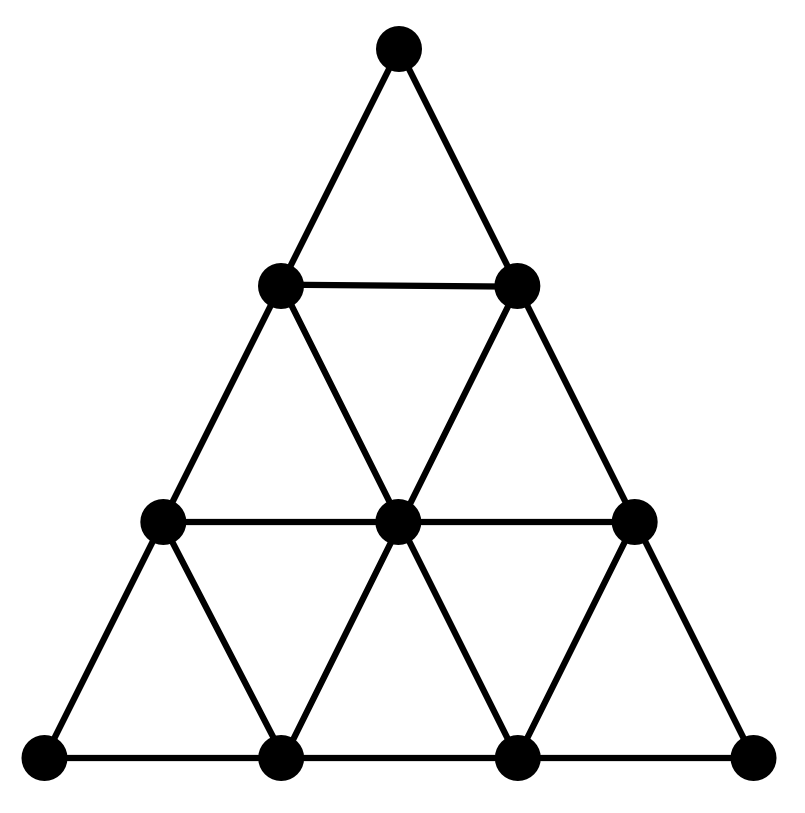

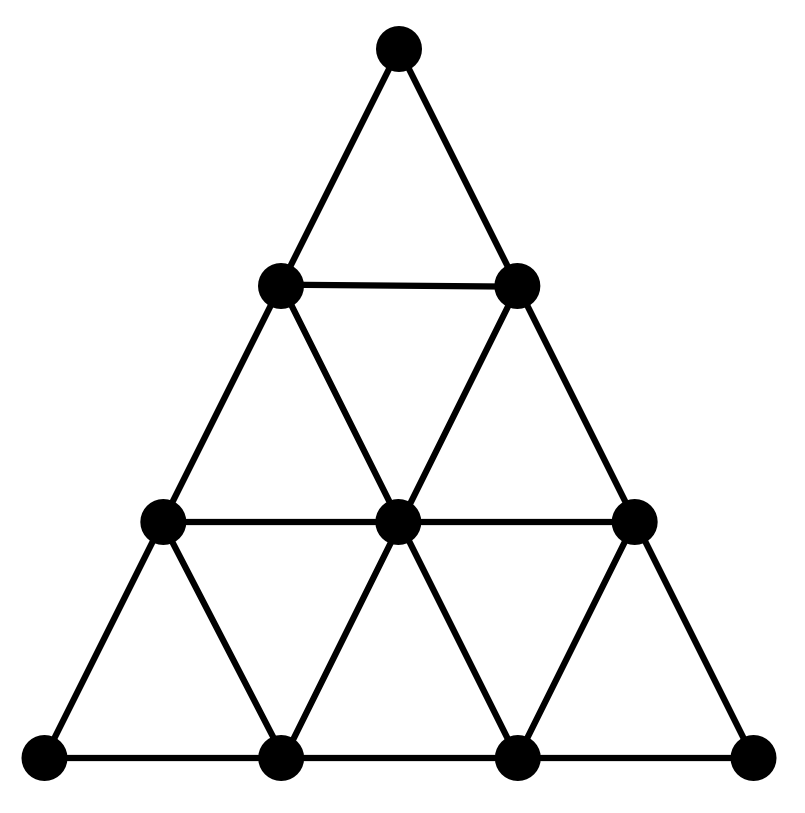

Tetractys

One of the most fundamental concepts of Pythagorean philosophy is that numbers have meaning. Pythagoras believed that the order of the cosmos and the mysteries of the universe were organised through the power of numbers. Numbers were comprehended not only as quantities but also as a guiding principle of creation that could ultimately reveal all the secrets of nature. Pythagoreans therefore diligently explored the symbolism of numbers as part of their contemplation of the divine principles of the universe.

The first ten numbers were thought to be sacred for the Pythagoreans. Amongst them, the first four numbers, which they referred to as the monad (1), the dyad (2), the triad (3), and the tetrad (4), as well as the number 10 (the decad), were most revered. The monad was regarded by Pythagoreans as being divine and at the origin of all things. The number 1 was deemed to contain in itself the potentialities of all other numbers. After the survey of the first nine numbers, the return of the number 1 in the form of the decad was, for Pythagoras, the sign of the most complete and universal expression of the monad, symbolising the perfect harmony in God’s arrangement of the universe.

The addition of the first four numbers 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 being equal to 10, the Pythagoreans held the triangular representation of the number 10 as their most sacred symbol – the tetractys.

Stay tuned, as we will describe the symbolic meaning of the first four numbers in the following posts on symbolism.

# 1

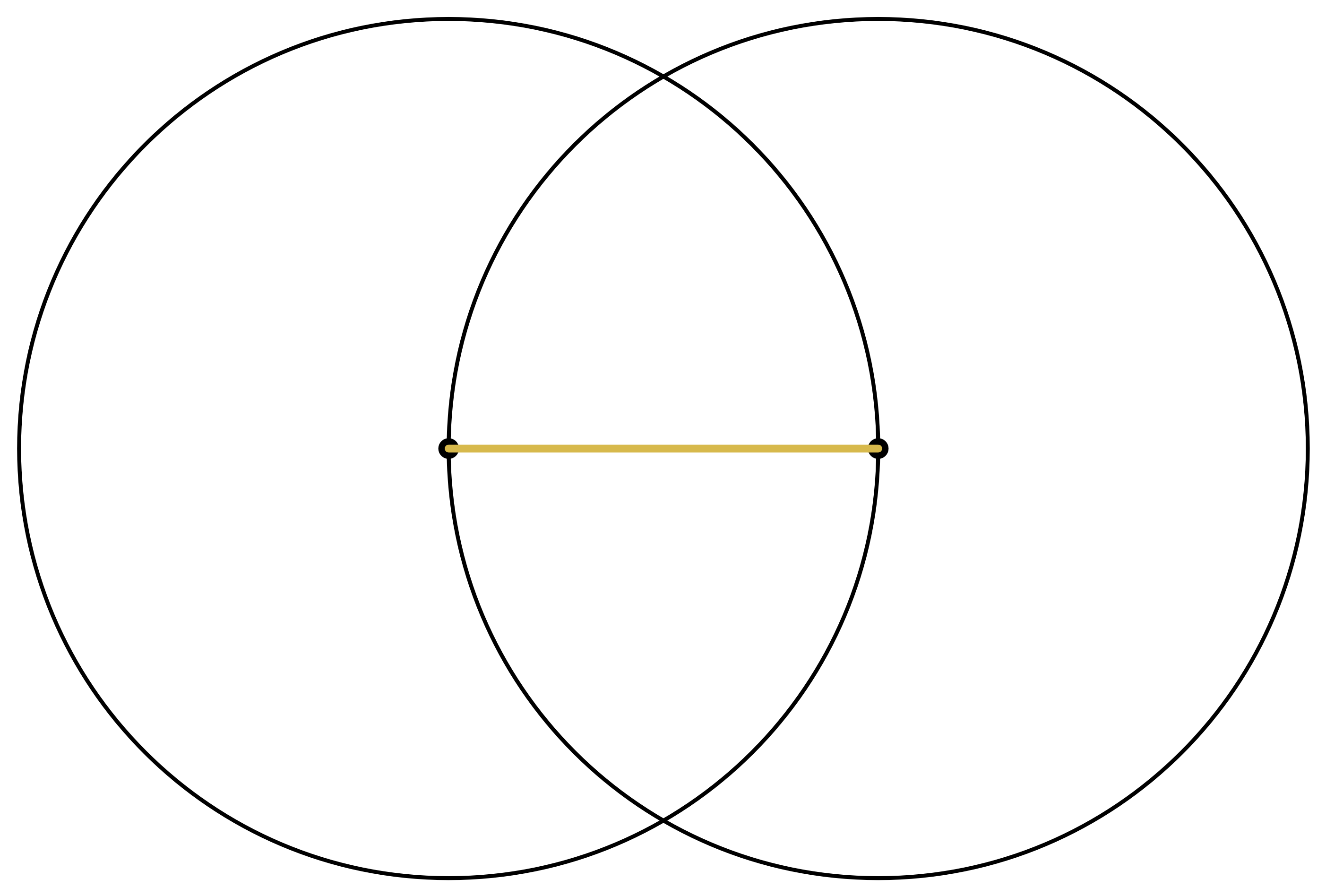

“God is a circle whose centre is everywhere and circumference is nowhere.” –Anon

The circle, along with the number 1, is traditionally the symbol of the divine unity, source of all things. For the Pythagoreans, the concept of the monad referred to the number 1 as the first divine principle. According to Diogenes Laertius, they believed that “The principle of all things is the monad or unit.”

The Pythagoreans allegedly used the image of the circle and the dot to represent it.

The circumference of the circle is a line which has no beginning and no end. In that regard, the circle is a symbol of eternity, timelessness, and the wholeness of God. The centre of the circle represents the origin, the seed, the source, and the non-manifested divine principle of creation.

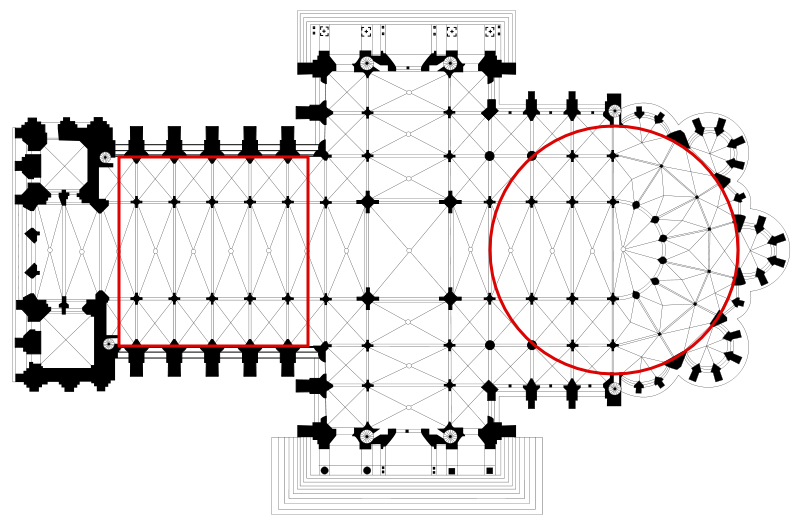

In Christian iconography, a circle is often drawn around the head of a saint as a halo, representing a glow of sanctity. Furthermore, in the vast majority of churches, abbeys, basilicas, and cathedrals, the sanctuary – the holiest place – is located in the eastern end of the building, and this is often delimited on its easternmost side by the semicircular space of the apse.

Chartres Cathedral*

In the Last Supper, the circle is hinted at in the shape of the decorative pediment above the door painted behind Jesus. However, beyond being a simple ornament, the circle is in fact crucial for the role it plays in the geometry of the door.

# 2

“Arising from this monad the undefined dyad or two.” – Diogenes Laertius

For the Pythagoreans, the principle of unity is such that it can only generate other numbers by replicating itself. Neither the multiplication 1 × 1 = 1 nor the division 1/1 = 1 can bring unity out of itself. Only the addition 1 + 1 = 2 is able to create a duality, which in turn begets the other numbers. ‘The dyad produces quantity,’ claims Aristotle.

Unity creates its own image. And as the circle replicates itself, the line which connects their centres is born.

The Pythagoreans called the dyad “audacity” (because it first separated itself from the monad) and identified it as the interval, or gateway, between the multitude and the monad. ‘The dyad is the medium between unity and number,’ writes Proclus in his commentary on Euclid’s Elements.

The number 2 symbolises the seminal principle of “otherness”, the primordial duality. It is also associated with the straight line, which, like a ray of sunshine, is a symbol of radiation and expansion.

The strong perspective lines suggested by the tops of the tapestries give rise to some of the most important questions in relation to the composition of the Last Supper. Their placement and their symbolic meaning are both beautiful and surprising.

# 3

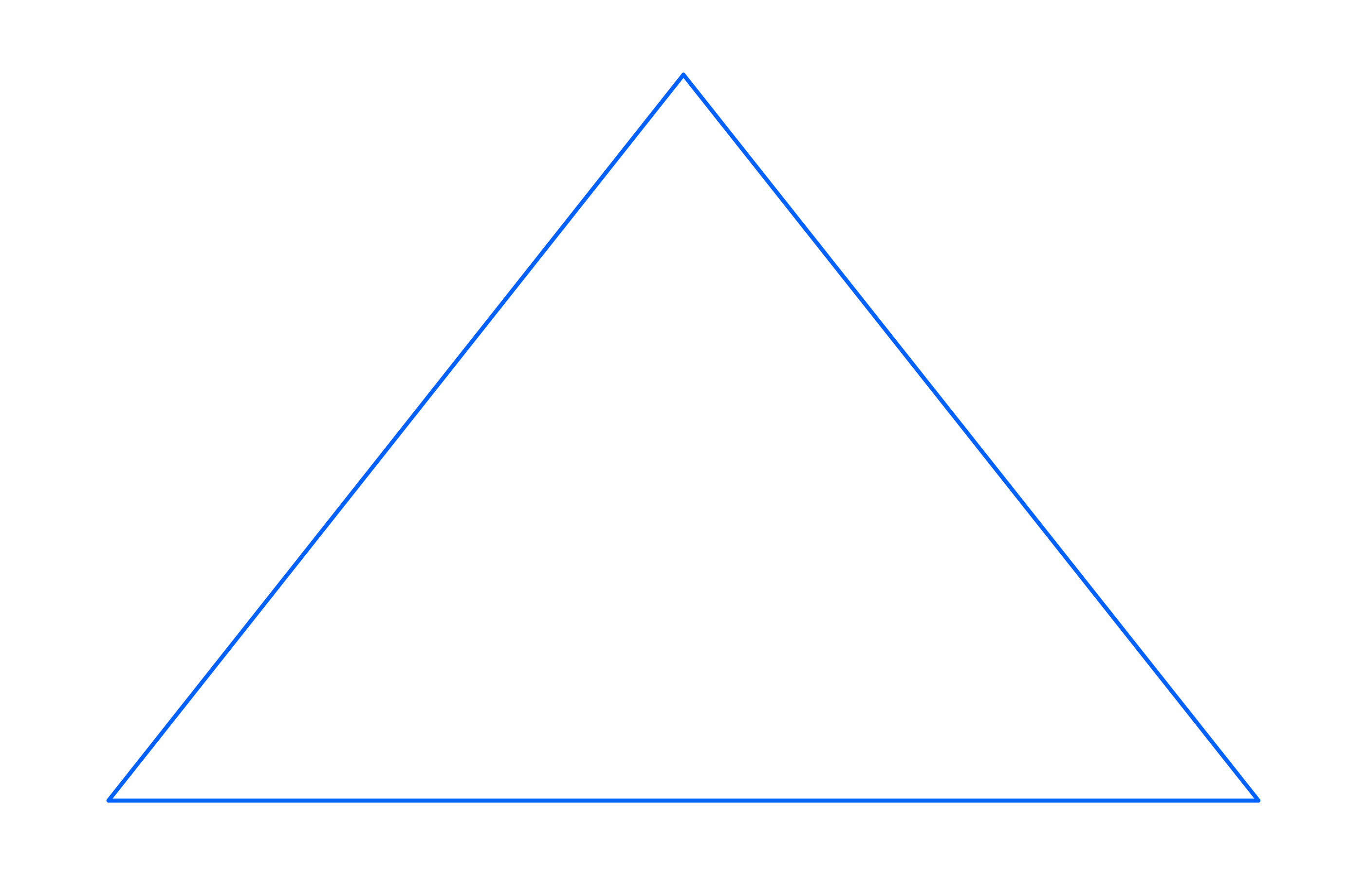

“But two things cannot be rightly put together without a third; there must be some bond of union between them.” – Plato

Inside duality hides the number 3: two protagonists necessarily exist in relation to each other. Similarly, two points are defined by the distance separating them. The Pythagoreans considered the number 3 (or triad) to be the first number, the monad and dyad being, above all, the two principles of the essence of all things.

The number 3 is represented by the triangle. First polygon to originate from the circle, the triangle is a symbol of the manifestation of the divine in all its creative power. The monad symbolises the infinite potentialities of an ineffable God, whereas the triad represents God as the Creator.

In the Christian tradition, a triangle pointing upwards is a symbol of God in the threefold revelation as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

The triangle symbolises plenitude and accomplishment. It is also a symbol of mediation where the reconciliation of opposites promotes concord, harmony and beauty. Finally, according to the first-century AD Greek mathematician Nicomachus, 'The triad also is intellect, and is the cause of good counsel, intelligence, and knowledge.'

Look for the triangle in the Last Supper, because it is the key that will unlock the whole geometry.

# 4

“For the divine number begins with the profound, pure unity until it comes to the holy four” – Pythagorean prayer

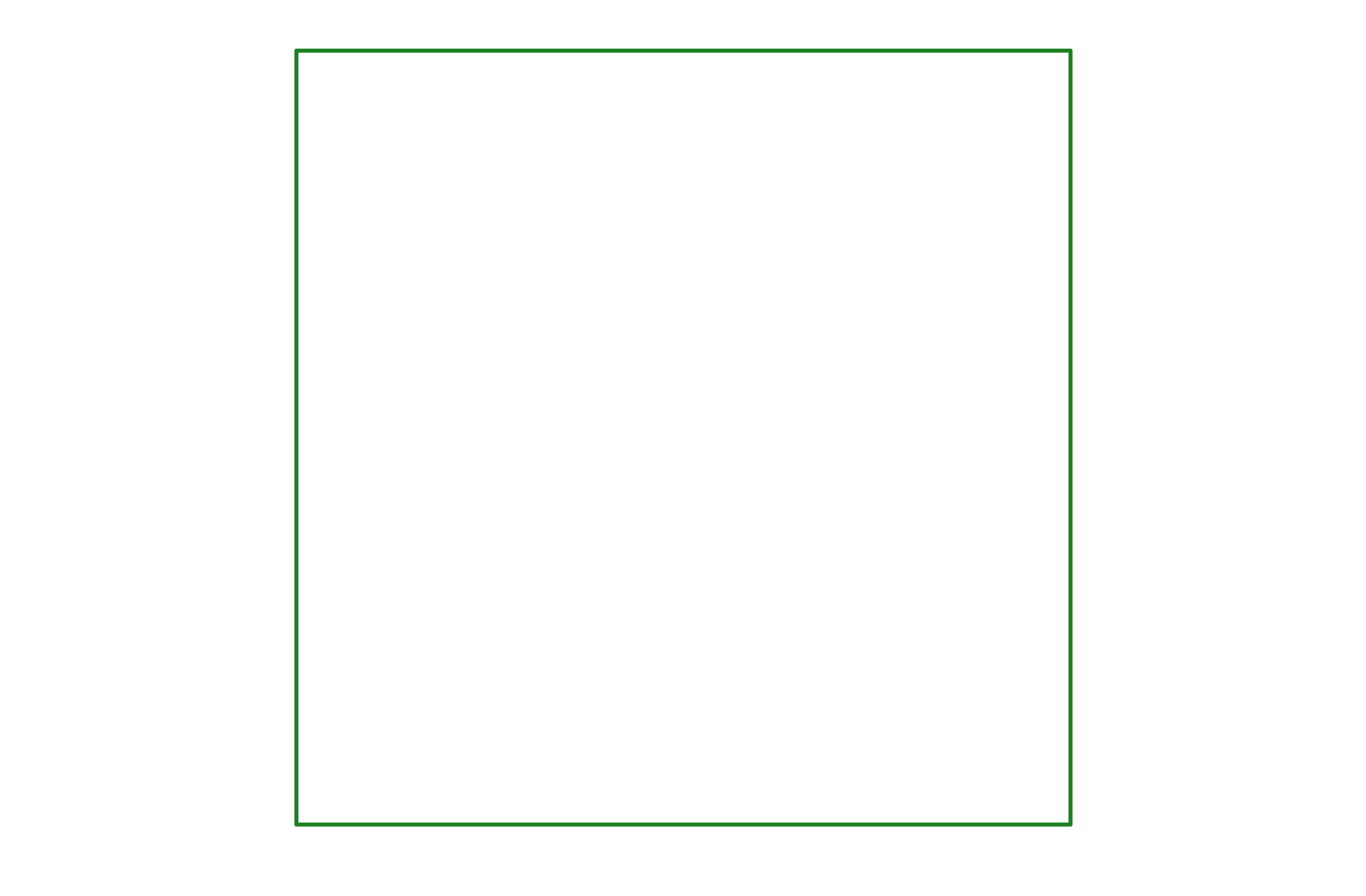

Whereas the triangle is a symbol of the divine world and the heavens, the created world is symbolised by the square.

There are four seasons, four cardinal directions, and the traditional four states of matter: fire, air, water, and earth. As a symbol of the cosmos, the earth, and matter, the square implies an idea of concretisation, limitation, and stagnation, contrasting with the infinite and seminal qualities of the heavenly realm.

We learn from Nicomachus that the Pythagoreans called the tetrad “the greatest miracle”. They revered the "holy" number 4 in the form of the tetractys.

The top of the tetractys is the monad and its base is the tetrad. As we might expect, the ascending movement from the base to the top (i.e. from earth to the heavens) carries a symbolism which differs entirely from that of the descending motion from the monad to the tetrad.

The square appears in the Last Supper as the canvas onto which the geometry is deployed.

Ascension

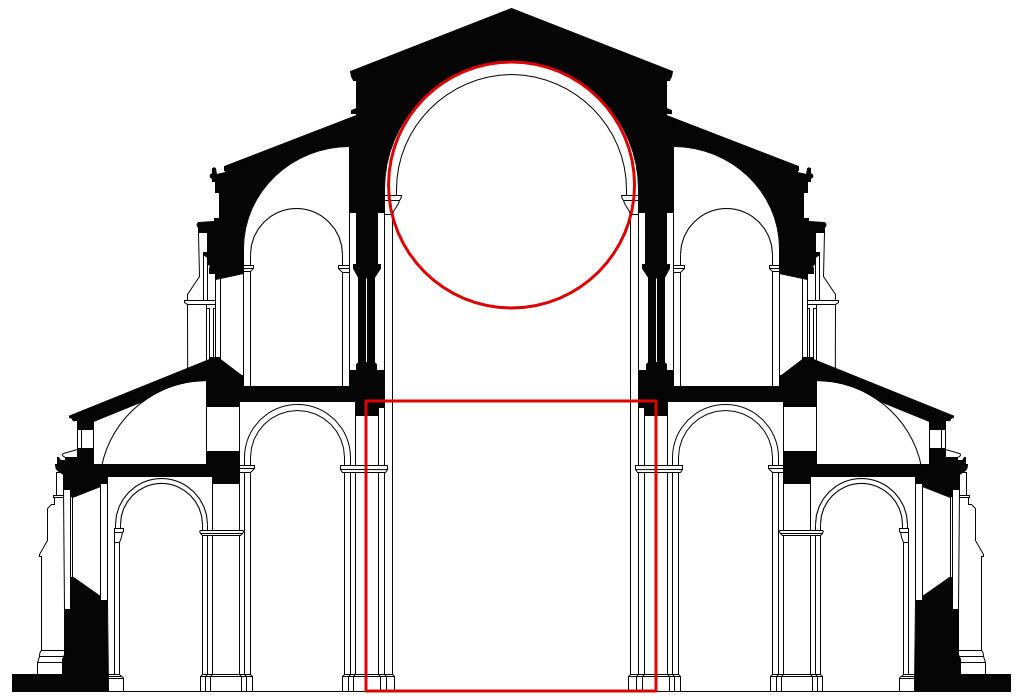

The ascension of the tetractys implies a return to the origin and an adherence to divine principles. The dynamic transition from the square to the circle therefore acquires a symbolic signification of purification, sanctification, and redemption.

The evolution of the earthly square towards the divine circle is a symbol of the spiritual journey of the soul towards God.

This symbolism is visible in the architectural organisation of sacred Christian buildings. The floor plans of many churches are based not only on the shape of the cross but also on the progression from the square to the circle. The footprint of the western side of churches is generally square or rectangular, whereas it is often circular at the eastern end.

In Chartres, for example, the congregation enters the cathedral from the west and, passing the narthex (the area delimited by the two square towers), find itself in the nave. Its progression towards the choir and the semicircle of stained glass windows projecting their coloured light on the altar below is intended to be an external manifestation of the inner spiritual journey towards the sacred.

The same concept is true of the elevation of many sacred buildings in Europe.

Saint-Sernin Basilica*

The semicircular vaults of Romanesque architecture (as in the Basilica of Saint-Sernin in France) gave way to the ribbed vaults of the Gothic style. The idea of the globe of heaven resting on the cube of the earth finds its most stunning realisation during the Renaissance, with the gigantic domes suspended over the transepts of Florence Cathedral and St Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

Conversely, the transition from the circle to the square represents the divine light condensing and becoming concrete in the reality of matter. It is a symbol of the process of creation, manifestation, and incarnation.

As astonishing as it might seems, the dynamic described here is present within the hidden message of the Last Supper.

Symbolic Outlook

From a symbolic perspective, the layout of the dining room represented in the Last Supper is very interesting. If we look at the lateral walls, we note that the number of tapestries hanging on each wall is four, a number symbolising our created world.

With the three apertures (consisting of the windows and the door) and the circular pediment above the door, the back wall features the numbers three and one, each a symbol of God, as the creator and principle of all things.

It appears then that the back wall, open to the light, symbolises a heavenly world, whereas the side walls and the foreground (including all the protagonists) represent our created world.

Could the geometry of the Last Supper be in tune with these two different symbolic worlds? The geometry behind Leonardo da Vinci's remarkable composition holds great beauty in its elegant simplicity, but it is its adequation with the symbolic nature of the work that truly makes it shine, like a blazing light at the heart of the Last Supper.

Stay tuned!

Subscribe